I don’t mean Spencer Strider’s velocity last night

In the midst of the Braves’ season going sideways relative to expectations, I think a lot about the team’s hitting approach (in case you can’t tell, ha). I wasn’t going to think about it at all, but the swap from Kevin Seitzer to Tim Hyers, the signing of Jurickson Profar, and various statements made by Hyers and Brian Snitker make it hard for me to not think about it at least a little. I have the following in mind:

- Steroids or not, Jurickson Profar is not a trade-contact-for-power batter, nor did he really do that in his “breakout” 2024.

- Both Tim Hyers and Brian Snitker have spent multiple media sessions talking about the importance of drawing walks.

- The broadcast mentioned that the Braves have a “chase rate contest.”

- Hyers’ initial remarks to the press involved discussion of “different ways to score.”

It’s really the last one that has persistently been at the forefront of my mind over the past few days. Going back to the series with Washington in Atlanta, the Braves outhomered their opponents twice and were outhomered once (both outhomerings were in Fenway Park) and went 1-1 while outhomering and 1-0 while outhomered. They were out-xwOBAed in four of those seven games, but won three of them. In the final two games in Boston, they had .400+ xwOBAs and wOBAs, and while one of those games had a three-homer outburst, the other had them plate ten runs with just one homer. Both of their Boston wins came with, and partly as a result of, a healthy dose of walks; taking three of four from the Nationals involved taking advantage of a poor Nationals defense despite not actually pounding the snot out of the ball.

To be clear, I don’t think there’s anything conclusive to be drawn from seven games, especially not when we’ve already seen multiple stretches of the Braves doing other weird stuff like very deliberately slapping at the ball. But, I do think the team is still tinkering and trying things — if not over the top, then in fits and starts as the players keep making adjustments that seem to be something different than “go ahead and miss as many strikes as you want so long as you’re up there trying to do damage and succeeding occasionally.” But, still, if you were going to try to walk more, chase less, and not focus solely on homers, I think you’d expect some semblance of more controlled swing, giving batters a split-second more to determine whether a swing was going to lead to a chase or not.

Which brings me to fastballs. (For these purposes, I am excluding cutters, because cutters are not generally used the same way a four-seamer or two-seamer is.) Going back to 2019, we have the following Braves xwOBA ranks, overall and against fastballs:

- 2019: 5th overall | 5th against fastballs

- 2021: 5th overall | 6th against fastballs

- 2022: 1st overall | 1st against fastballs

- 2023: 1st overall | 1st against fastballs

- 2024: 7th overall | 9th against fastballs

(Remember that 2019 and 2021 still involved pitchers hitting for the Braves, but not 15 other teams.) The idea here is pretty consistent: the Braves hit very well, and hit fastballs very well as part of that. In 2025, though?

- 2025: 12th overall | 20th against fastballs

Why am I thinking about fastballs, directly? Well, specifically because of last night. The Braves jumped on Mitchell Parker for three runs in the second inning. In that second inning, Parker was still fastball-heavy (53 percent), but he threw the same number of fastballs as curves after Matt Olson homered on the fourth straight fastball he saw, and the Braves ended up with a .680 xwOBA inning.

After that, Parker threw more fastballs (57 percent, albeit, not dramatic) and more evenly mixed his three secondaries, and the Braves managed just a .153 xwOBA against him the rest of the way. If you want to be more generous to my in-the-moment observation, it’s that Parker threw way more two-strike fastballs after the first two innings (62 percent of the time, compared to one two-strike fastball which was then hit for a homer in the first two innings), but I’m comfortable saying my observation was off, even if it prompted this post anyway.

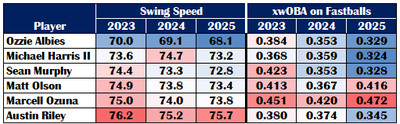

By definition, you have less time to react to fastballs. Taking an extra beat could matter. I put together the following table, which isn’t meant to be instructive, just more thinking about whether the Braves are gimping themselves on fastball damage:

From this table alone — not really, or at least, not team-wide? Have most players gotten worse on fastballs? Definitely. But only Ozzie Albies, Michael Harris II, and Sean Murphy are both swinging more slowly on fastballs and lacking oomph on them. Austin Riley has also decreased in the oomph department, but his swing speed hasn’t been hit the same way. Whatever Matt Olson and Marcell Ozuna have implemented could be working for them, but it’s hard to say the other guys have had the same experience. (Or it could just be noise.)

Disclaimer: the table above shows swing speed only for the second half of 2023, because no first half data are available; xwOBA on fastball includes cutters because I was too lazy to remove them from the query here.

Anyway, there’s probably more work to do to delve into the Braves and fastballs. I’ll just leave this with the note that of all these regulars, the only guy to have meaningfully improved his chase rate from 2023-2024 is Ozuna. Riley’s chase rate has actually collapsed at the same time. So, so much for the chase rate contest in and of itself, I don’t think that’s helping teamwide, if they’re still even doing it.

Daily Notes

Record: 24-24

Yesterday’s wOBA and xwOBA: .280 / .286 (Season rank: 14th | 12th)

Yesterday’s wOBA and xwOBA allowed: .369 / .363 (Season rank: 15th | 13th)

Yesterday’s homers: 1

Yesterday’s homers allowed: 1

Record when out-xwOBAing: 15-10 (League: 523-191)

Record when out-xwOBAed: 9-14 (League: 191-523)

Record when out-wOBAing: 20-3 (League: 608-109)

Record when out-wOBAed: 4-21 (League: 109-608)

Record when outhomering: 10-4 (League: 373-107)

Record when outhomered: 5-12 (League: 107-373)